.

While looking for baby pictures of my daughter, per her request, I rummaged through a shoebox of Kodachrome people trapped in manufactured moments and found a photograph in which I was sitting across my mother’s lap. The lawn we’re relaxing on is familiar to my imagination. Whether I’ve imagined the correct location doesn’t matter. Facts are irrelevant to this feeling.

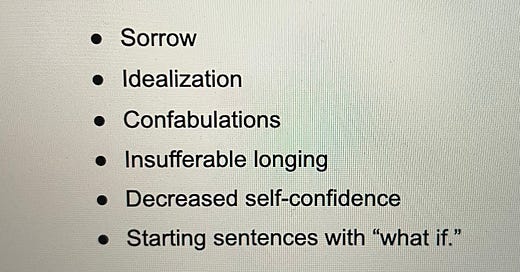

Exaggerations happen. Nostalgia’s tyranny enslaves the unguarded and turns wishful thinkers into romantics.

Not all tears form a liquid.

The photo is from 1982, a faded relic more realistic than the absurdly clear and vibrant photographs of today’s technology. I was two years old in ’82. My mother was 21. We are wearing tank tops and, it seems, enjoying the nice weather while, on the surface, doing nothing, but internally, physically, and telepathically, we’re forming a bond strong enough to withstand all my future mistakes, a bond I have sometimes lost sight of and taken for granted.

In the photograph, my mother has long brown hair, a blanket over her legs, one arm around my back, and her fingers wrapped around my ribs, resting just below the underarm. I’m holding a green one-liter bottle. The jagged plastic ring encircling the bottle’s mouth appears to amuse me. I’m unaware she’s staring at me. We’re both mesmerized, only for different reasons.

Behind my mother, abutting the photo’s top edge, are the railing and balusters of an elongated porch attached to a white house lost to the limits of the absent camera’s focus, a home where many Christmases were spent, setting the bar for what Christmas meant, long forgotten but still dreamable. My observations are based on hope, though. I don’t know whose house it is. I can’t see it in the photo, so I imagine it belonged to my grandparents before their many renovations. I can only imagine and do so because, despite the thick miasma of cigarette smoke and my grandparents’ alcoholic lifestyles, that house was unadulterated magic to me, that is, until somebody rolled the hospital bed out of the living room and relatives fought over belongings.

The photo has since been on my desk, leaning against a stack of books, coincidentally below the title: The Progress of Love. It’s a familiar photo, nothing new. I don’t know why I’m suddenly attached to it. But I know it embodies hope.

Kierkegaard said nothing was more dangerous to him than recollection. I’m tempted to apply that statement to me because looking back has only ill effects, regardless of whether the event was good or bad. However, drugs and alcohol are likely more perilous to me than remembering. Perhaps the chemicals I used to ingest daily contribute to why I detest peeking at the past—why it’s so painful: the missed chances, the wasted days and forgotten years, the misremembered loves, the disappointments I caused others, and the fears, oh, so many fears, all lingering, burrowing deeper into my consciousness with each word I write to distract myself from what could’ve been.

As I analyze my mother’s profile, I wonder if she’s ever been aware of her beauty. I notice her head is tilted to her left, her face slightly downward. Her facial expression is caught between awe and perplexity, almost as if she were thinking, “What is this feeling?” It’s a subtle and unbidden smile, one of rapture and enchantment. She has no clue a world exists beyond the curls covering my forehead. There are no bill collectors, no insecurities, and no worries. Her life seems perfect at that moment.

But life moves forward. The flow of time gives us only one direction, toward decay, and everything stays in motion, away from our finalized decisions, the causes of our effects. Resentments form. A trail of consequences drags from our feet like immovable toilet paper stuck to our shoes. We tumble or fall, sometimes get stuck, and are forced to untangle ourselves—to remember—to face reality. Either we stand or crawl or don’t move it all.

My mother still believes in me, that I might one day climb out of the mess I’ve spent thirty years making. She still feels I might make something of myself. Maybe become a responsible adult.

At least one of us still has hope.

I feel I will forever be tangled. Forgotten consequences continue to resurface and knock me down. New consequences happen daily, which is impressive for a guy who rarely leaves the house. I keep tripping over myself. But, thanks to my mother, I’m still standing.

A marvellous tribute. Here's to mothers leaving the light on.

Moved to tears. This is beautiful.